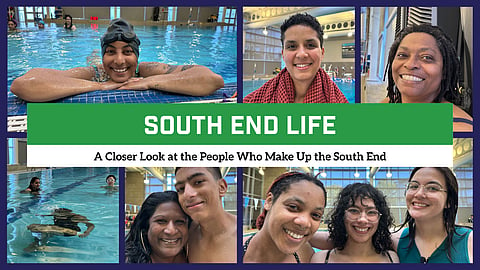

South End Life: Communities of Color Explore Their Relationship With Water, Learn to Swim

"There is a reclamation that I engage with in water," said Alanna Francis, Oshun Swim School instructor. "Water is gatekept … especially if you're Black."

Alanna Francis described how her Black father had limited pool access in the American South and couldn't learn to swim. She also says private waterfront developments limit public access to water. Noting that up to 60% of our body mass is water, she said, "Being able to reclaim the water is also reclaiming our bodies."

Last year, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study found that 63% of Black Americans have never taken a swimming lesson. In King County, preventable drownings increased from 16 cases in 2019 to 25 cases in 2024. Black and African American drowning rates were twice the county average in the most recent study.

Seattle Parks and Recreation has partnered with Oshun Swim School as part of the Swim Seattle initiative's effort to remove barriers to swimming opportunities. Oshun Swim School takes an Afro-Indigenous, healing, and trauma-informed approach to encouraging BIPOC communities to explore their relationship with water, and it offers a space to learn to swim.

Chezik Tsunoda, a Black filmmaker and mother of a son who drowned, has since founded No More Under, an organization dedicated to saving lives through water safety education and equitable access to swim lessons. Unlike what we see in films, drownings are quiet and can happen within 20 to 60 seconds. And while drownings are preventable, they are currently the leading cause of death for children 1 to 4 years old.

South King County resident Chandrika Francis (no relation to Alanna) is the founder and a facilitator of Oshun Swim School. She started this type of work when she had a job taking inner-city youth from Oakland on outdoor and backpacking trips.

She recounted an outing where a rope had been left behind from a previous campsite. She said the youth commented: "They're gonna hang us out here." Chandrika Francis said, "You know that they were joking, but racial trauma was coming up. They're having to contend with the possibility of racist violence when we go into the wilderness." She added, "Whenever you're working with Black and Brown people in this country [and] connecting to earth or water, layers of historical violence come up."

Water sites were locations of extreme violence to Black American communities. Black people were forcibly transported from Africa to the United States in ships, and bodies of water were often the locations of lynchings or a place to deposit Black bodies. But, according to studies, the West African diaspora historically had a strong relationship with water as skilled seafarers. Many West Africans and Black Americans were skilled swimmers (more so than most white people in the U.S. during slavery) until enslavers suppressed swimming, worried it would be a means of escape. During Jim Crow, water was used as a weapon: Access to water for drinking and recreation was limited, and fire hoses were used on peaceful civil rights demonstrators.

Chandrika Francis says she had been incorporating trauma-informed practices for a long time, but she noticed a shift in people's connection to the water when she incorporated information about the West African deity, Oshun, into conversations at the pool. Oshun, the namesake of the swim school, is an orisha, or deity associated with fresh water, healing, pleasure, and protection. Chandrika Francis says she's not attempting to promote a religion, but she has seen how conveying the historical context of ancestral connection to water offers a helpful perspective to participants.

"Part of decolonizing the way that we teach swimming, especially Black and Brown people, is by leaning into our ancestral way of connecting with water. In every West African practice that I'm aware of, which is where most Black Americans come from, water is inherently a spiritual place, [a] connection to the ancestors," Chandrika Francis said. "I've seen people who have trauma around water having that connection, knowing they are connecting with their ancestors by connecting with water, has opened up space for them to have a different experience in water."

Marie Angeles, a South End participant in the June open swim program held at Rainier Beach, floated on a foam noodle in the Rainier Beach lap pool and described how she works through learning to swim. "Somewhere in my body, there is a lineage of somebody who could comfortably be out in the water all day, every day and go to the greatest depths. Accessing that when I'm swimming helps to release and have trust."

Tea Tinsley, who's a teaching artist and used to live in the Othello neighborhood, says she started learning how to swim through Oshun and has been leaning into being a swim instructor. She says she's also been "mermaiding" for organizations like Families of Color Seattle for about two years. When Tinsley mermaids, she dresses as a mermaid and speaks with the audience about Afro-Indigenous water spirits, like Oshun and Yemaya (queen of the sea).

At the Oshun Swim School, open swim starts with a circle so people can share what they would like to get out of the class. People who want to just float and stand in water group up in one area, while those who want to learn swimming skills gather in another. People learn at their own pace.

Tsunoda says there are a lot of things that can make you uncomfortable around water. "There's body image, hair, the lack of swimming, PTSD, and also being [in] a very white space is also uncomfortable," said Tsunoda. "I remember a woman saying there was nothing like having a Black swim instructor show her how to put on a swim cap."

Moxie-Svetlana Hubbard-Shirley has been with Oshun for about a year and a half. Hubbard-Shirley recounted a terrible experience that she had of being flung off an inner tube by an older white man when she was younger at a wave pool. She says she kept this story suppressed until more recently. When she had her two daughters, she was determined to send them to swimming lessons.

After Hubbard-Shirley shared her story about the wave pool, she looked over at her two daughters on the deck with a wide grin as they dove into the pool simultaneously. She says Chandrika encouraged the daughters to take on a Black lifeguard certification training, and they would be testing for it soon. "I can't wait until they become lifeguards. I'll be the hypest mom ever," Hubbard-Shirley said.

Then, after a short pause, she smiled and added, "And then maybe I might become a lifeguard."

South End Life Bulletin Board

July 4 Tips for Helping Pets Cope

Fireworks aren't always our pets' best friend. Check out before, during, and after tips from King County to prepare your pet for Independence Day sounds and tremors.

Fireworks Can Mean Air Quality Issues

Washington state, county, and federal agencies and tribes have partnered on this smoke blog to track air quality.

Before You Go Swimming in a Lake

The Washington State Department of Ecology posts the locations of algal blooms that are harmful to people, pets, and wildlife.

Yuko Kodama is the News editor for the South Seattle Emerald. She is passionate about the critical role community media plays in our information landscape and loves stories that connect us to each other and our humanity. Her weekly "South End Life" column spotlights the stories of neighbors and community members that weave through the South End.

Help keep BIPOC-led, community-powered journalism free — become a Rainmaker today.