31 Days of Revolutionary Women, #15: Anne Braden

In honor of Women's History Month, we present 31 Days of Revolutionary Women; a series ofdaily essays by local authors documenting, honoring and celebrating powerful women who inspire usin South Seattle and beyond.

by Lola E Peters

The room buzzes with pre-meeting chatter. It's my second or third time attending these meetings and I'm just getting to know people I would grow to respect and love over the coming decade: Ron Chisom of The People's Institute for Survival and Beyond; Joe Barndt, founder of Crossroads; Nozomi Ikuda, United Church of Christ leader; activist and organizer, Dr. Loretta Williams; Kaleo Patterson, organizer for Native Hawaiian rights.

A small, White, gray-haired, wiry woman sits in a cushioned, hard-backed chair. As each of the twenty or so attendees enters the room they make their way to greet her, always with deference and affection. We begin another gathering of the National Council of Churches Racial Justice Working Group by introducing ourselves for the sake of newbies, like me, and speaking about our lives and the work we are doing professionally.

When it's her turn, the White woman introduces herself as Anne Braden, founding member of the Southern Organizing Committee for Economic and Social Justice (SOC). She speaks about SOC's work and their growing partnership with environmental organizations, and adds a little bit about her children. She is direct and plain spoken, and she shows a wry sense of humor. Still, among the extraordinary people in that room, she seems rather plain. I talk with her during several breaks over that weeklong gathering, having only the impression of a humble, yet steel-spined, elderly woman.

There was no Google then, so it happened that nearly a year later I mentioned Anne Braden's name to a friend and learned that the deference and affection shown her in that meeting were not simply conferred out of courtesy, but out of deep respect and honor. Anne Braden didn't wear pink hats or safety pins. She didn't hug people of color and wring her hands at how bad things were. Anne Braden changed the history of the United States, repeatedly.

Born Anne McCarty in 1924 Louisville, KY to a family steeped in the southern racist tradition, and raised in Anniston, AL, she had the opportunity to go merrily along in a lifestyle of teas, book circles, fashion, monetary inheritance, and charity work. That she attended college speaks to her family's affluence and influence. She chose, instead, to leave it all behind to rectify one wrong: by adopting White supremacy people of European descent were losing their humanity, their souls.

Seeing the injustice White people in her family and community routinely put upon or ignored toward Black and Native American people, she saw racism as their spiritual and moral death. Determined to fight racism in order to save her own people, she put her whole self, her very life, on the line.

She began as a newspaper journalist. As she researched and verified stories she became aware of the inequity in the administration of the law. She saw how Whites were treated less severely when accused of the same crimes as Blacks. She saw that Blacks and Native Americans were openly accused of and punished for crimes they obviously did not commit. She saw the inequity in job opportunities, education, and housing and the inevitable consequences. She admitted that White people were not superior in intelligence, talent, or integrity but were steeped in a rigged system that required their collusion resulting in their moral destruction and self-delusion.

In 1950, Anne led the charge to desegregate hospitals in Kentucky. She was first arrested in 1951 when she organized a group of southern White women working with the Civil Rights Congress to protest the conviction of Willie McGee, an African-American man convicted of raping a White woman in Mississippi.

In 1954, the same year the U.S. Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education, Topeka, KS, Andrew and Charlotte Wade, African-American acquaintances of Anne and her husband Carl, wanted to buy a house in the Louisville suburb of Shively, but exclusion clauses, routinely present in most White communities, banned African Americans from purchasing homes there. After months of frustration, the Wades approached the Bradens with a request: would the Bradens purchase a house for them. The Bradens readily agreed.

Once neighbors realized a Black family had moved in, they burned a cross on the Wades' lawn, shot out windows, and began a campaign against the Bradens. Six weeks later, while the Wades were out, the house was dynamited. The case was never solved.

The Bradens then were accused of being communists and eventually charged with sedition, along with five other White "co-conspirators". Carl Braden was found guilty and sentenced to 15 years in prison in October1954, but was released on bond in 1956, then released when the US Supreme Court ruled in a similar case (Pennsylvania v. Nelson) that state sedition laws were invalid.

Blacklisted in the McCarthy era, the Bradens were unable to find jobs so they founded an organization in New Orleans to build White support for the Civil Rights movement. They began their own monthly newspaper, The Southern Patriot, and printed pamphlets and other progressive documents.

Anne's Wikipedia entry says of her 1958 memoir:

One of the few books of its time to unpack the psychology of white southern racism from within, it was praised by human rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Eleanor Roosevelt, and became a runner-up for the National Book Award. Although their radical politics marginalized them among many of their own generation, the Bradens were reclaimed by young student activists of the 1960s. They were among the civil rights movement's most dedicated white allies.

She and Carl continued to fight racism. Rather than seeing herself as an ally to the Civil Rights movement, Anne saw the movement as her partner in liberating her own family, friends, and community and restoring their humanity. Three days before she died in 2006, Anne completed a proposal for an activist summer camp. She was a resister to the end.

As I watch Diana Falchuk, Ilsa Govan, Julie Nelson, Robin DiAngelo, and other White women in our community develop their antiracist path, I'm reminded of Anne and pray to her spirit to guide, cajole, irritate, succor, sustain, and show them courage to actively bring about the liberation of their own people by destroying racism at every turn.

Lola E Peters is an essayist, poet, and anti-racism organizer who lives in West Seattle. Her book of essays, The Truth About White People, is available at Elliott Bay Books and through most major online retailers. Read more about her at http://lolaepeters.weebly.com.

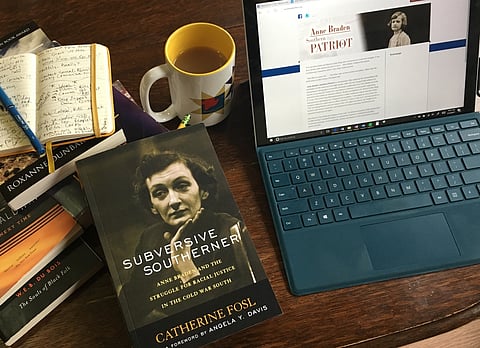

Featured image "Morning Research" by Marilee Jolin

Help keep BIPOC-led, community-powered journalism free — become a Rainmaker today.