"First They Killed My Father" Stirs Reflection In Cambodian Genocide Survivors

by Sharon H. Chang

It was not that long ago when the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), also known as the Khmer Rouge, seized control of Cambodia and murdered around 2 million people in one of the worst mass killings of the twentieth century.

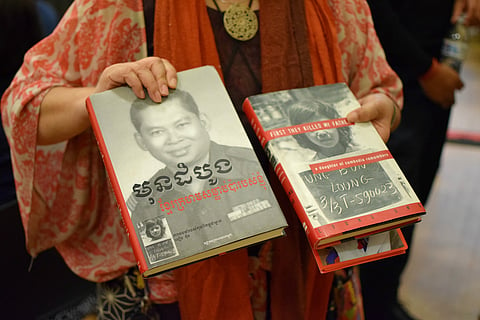

Almost 158,000 Cambodian refugees fled their homeland and gained entry into the United States. Twenty years later Loung Ung, Cambodian American survivor of the genocide, published her pivotal debut memoir First They Killed My Father: A Daughter of Cambodia Remembers.

And then last week, three decades since the brutal regime fell, everyone got the chance to see something even more pivotal–Ung's memoir transformed into a film and released to the world.

First They Killed My Father, the movie, launched globally via Netflix September 15. Loung Ung, now author and human rights activist, co-wrote the screenplay with Hollywood celeb and U.N. Ambassador, Angelina Jolie (who also directed). The two women met after the celebrity read Ung's book and was mightily impressed. They decided to collaborate. The movie was filmed by a Cambodian crew, co-produced by Cambodian auteur Rithy Panh, and was just selected by Cambodia as their official foreign language entry for the Oscars.

In Seattle, home to around 20,000 residents of Khmer origin, a special community screening was organized last Friday by University of Washington's Khmer Student Association (KhSA). The screening was held at Asian Counseling and Referral Service (ACRS).

First They Killed My Father is artful, sensorial and harrowing. Shot from Ung's perspective under the regime as a child aging from five-to-seven years old (portrayed by Sareum Srey Moch) the film seems far less interested in conveying historical fact than it is in conveying the confusion, fear and disorientation that ate away at those living through the horrific time. From the opening scene the movie disturbs in visceral ways that unhinge the psyche and spirit.

But in Seattle one of the most compelling moments of the screening actually came after the viewing–when a KhSA-organized panel of local Cambodian genocide survivors reflected upon the film through the lens of their own experiences.

Vanna Evanson had to walk past dead bodies and be careful of landmines just like Ung's young character. The movie also portrayed the psychological abuses of the Khmer Rouge which Evanson remembers all too well. "You see [in] the movie already the culture," she pointed out. "You cannot cry, you cannot have emotion show. Everything just made me hate Cambodia."

Evanson said she used to ask herself, "How can this person, is Cambodian, speak the same language as me and we eat the same food and they don't understand me? Why do they kill? Why do they do stabbing?" Seang concurred, "It was just fighting and killing each other. Nobody can understand anything just like you see in the movie in the eyes of the girl."

Moderator Sameth Mell came to the U.S. as a refugee as an even younger child. Mell and all three panelists lived as children at Khao-I-Dang refugee camp for some time before being selected with their families for sponsorship to the United States.

Mell had recently returned from Cambodia where he leads Khmer Americans on trips to reconnect with their history. His last group, he shared, visited the Tuol Slen Genocide Museum and returned to Khao-I-Dang which just reopened in May 2016. There is not much at the former camp site anymore, said Mell; a small museum, the Khao I Dang mountains, a lake, a spirit house and remnants of a temple, and the caretakers home. But Mell encouraged Cambodians in the room to go back and visit if they can.

Everyone in Cambodia and anyone that is Cambodian American now is impacted by the legacy of the genocide, Mell reminded the audience, and talking about the past is emotional but paramount. Panelists agreed confessing they themselves do not talk about the genocide much but still think doing so is meaningful.

Sean said, for instance, when his kids face life hardships he will share his stories to help strengthen them. Evanson has taken her children back to Cambodia to show them places where she suffered. Ultimately it is important, Evanson advised, to know what hate can do to people.

"A lot of this trauma we've seen resonates . . . with a lot of different communities," remarked Savannah Son, "and it still resonates today in our community." The KhSA President thought to herself a moment, then finished wisely, "It re-imagines itself every day in our lives and it's important to think about how do we heal from that and [. . .] how do we hold these kinds of stories."

KhSA is holding another screening October 16 of Daze of Justice, a film that follows Cambodian American survivors from Long Beach, California, as they travel back to Cambodia to testify against the Khmer Rouge. The director and presenters will be present to discuss intergenerational trauma. Location on the University of Washington campus TBD. Check KhSA's Facebook page for details.

Sharon H. Chang is an activist, photographer and award-winning writer. She is author of the acclaimed book Raising Mixed Race (2016) and is currently working on her second book looking at Asian American women and gendered racism.

No Paywalls. No Billionaires. Just Us.

We're raising funds to hire our first-ever full-time reporter and grow our capacity to cover the South End. Support community-powered journalism — donate today.