Fiction: All the Boys

by G.G. Silverman

She was 13, but didn't know how old the boy at the basketball hoop was. He was cute. Maybe 16? He played alone in the long twilight of summer. She hadn't seen him before. He might've lived here his whole life but hadn't gone to her school — maybe he went to private school? — and only now discovered the hoop next to her house, by the lone street lamp on the road. Didn't notice her, even though she sat on the wall close by every night, watching. He seemed all-American and tall and tan and smooth and quiet and she swore his sweat smelled delicious like ripe apples. She loved his close-cropped hair and the soft light fuzz at the nape of his neck. He hardly uttered a sound as he practiced layups, and she admired his movement, his ease. She wondered more about him. She clapped when he sank the ball again. She wondered if he'd grow to like her, if she'd become his girlfriend. Then she could go to his house and listen to records. Then maybe his mom and dad might ask if she'd come get ice cream with them at the diner by the lake. Maybe he'd hold her hand in the back seat of the car where his parents couldn't see. Maybe he'd steal some of his dad's aftershave and slap it on his peach-soft skin.

She nursed this fantasy every night at the hoop. She'd try to seem interested in the boy. Maybe someday he'd ask if she'd take a shot. She'd say yes. She could do layups as well as anyone.

For a long time, he said nothing. So she became vocal, saying, "Nice shot!" whenever he nailed one. He mumbled his thanks.

Finally, one day, he asked, and she quietly slid off the wall. She caught the ball he tossed at her and shot a layup the way she'd learned in gym, gliding over and up, sinking the ball with one smooth movement.

The boy said, Nice.

He tossed the ball again, and they played in silence until it was dark and he said, I have to go.

They parted. She glanced at his smooth nape as he walked away without so much as a wave, and his long limbs carried him toward the big white house on the hill a few doors down.

She still didn't know his name.

As July became August, this was their routine. She'd watch him shoot hoops until he invited her to do the same.

One night she waited for him. When he finally came, hands shoved in his pockets, he asked, Wanna come over?

Yes, she said.

She thought, Maybe I will meet his mother. Maybe we'll listen to records. Maybe we'll have ice cream. Maybe we'll slip away from his parents and walk through the woods by the lake, ice cream dripping down our hands until they're sticky-sweet, then maybe we'll kiss, and it will be sugared and filled with longing.

He said, Come by my house in 5 minutes.

She said, Okay.

She sat a moment until the excruciating minutes passed, then strode up the road, curious. Excitement needled her skin.

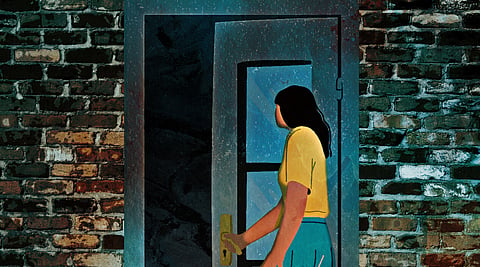

The boy's big white house was stately, nothing like her small one. She trod up the concrete stairs that zigzagged over a retaining wall and a hill of green at the top. She walked up more stairs to the front door, and it was partially open. She pushed it a little wider. She stepped in, straddled the threshold, one foot in, one foot out, body bracing the door between worlds.

In the room, it was more than just the boy. It was more boys, all boys. And they sat back in the way that boys did, confident that the world was theirs, legs spread so their jewels could breathe, the violence of their bodies hidden and lying in wait. And the one who invited her patted the couch beside him, summoning her. In that moment, everything that lay before her made itself known, all the lives she could live, and the ones she didn't want, and all the boys who would ensnare, traps bloodying her limbs if she dared step in. And she froze there, a rabbit in the path of a hunter, not a single twitch of a whisker. She spun, fled the way she came, feet pounding pavement, slamming the door on the traps and the boys and all the lives she didn't want.

Featured Image: Composite based on original illustration by Lemono/Shutterstock.com; editing by Emerald team.

Before you move on to the next story …

The South Seattle Emerald™ is brought to you by Rainmakers. Rainmakers give recurring gifts at any amount. With around 1,000 Rainmakers, the Emerald™ is truly community-driven local media. Help us keep BIPOC-led media free and accessible.

If just half of our readers signed up to give $6 a month, we wouldn't have to fundraise for the rest of the year. Small amounts make a difference.

We cannot do this work without you. Become a Rainmaker today!

Help keep BIPOC-led, community-powered journalism free — become a Rainmaker today.