Some Detained Protestors Must Wait at Least Six Months for Own Arrest Records, Hampering Legal Efforts

by Carolyn Bick

Seven days after Aisling Cooney filed a public records request with the Seattle Police Department (SPD) to get her own arrest records and associated materials from her arrest at the Capitol Hill protest on July 25, the records department succinctly informed her in an email that these records wouldn't be available to her until late February 2021.

Cooney isn't alone. At the advice of lawyers with Smith Law, at least four others who have also filed for their arrest records — as well as associated documents, recordings, and more — as part of several civil lawsuits they hope to bring against SPD have received similar messages: the SPD's Legal Unit is "operating under an extreme backlog of requests, staffing shortages, the redeployment of supporting units to SPD's frontline COVID-19 response, and, pursuant to CDC recommendations and City direction, reassignment to remote access."

"For these reasons, our ability to process new requests is substantially limited; we are currently estimating minimum response timelines, depending on the volume and complexity of requests, in excess of 6-12 months," the records center's initial notification to both Cooney and fellow protestor Jordan Riggs reads.

On its face, the inability to quickly get one's own arrest records might appear to be more of a frustrating inconvenience than a problem. But Sad Smith of Smith Law — whose firm is representing members of this group in a suit filed in federal court, the planned civil suits, and several other clients involved in protest actions since early June — said otherwise. In fact, she said, it's a huge problem that means the planned suits are at a standstill, and lack of information is its crux.

"If you don't know what the allegations are, you can't contest those allegations, you can't potentially follow up and file suit — there's just no remedy without that information," Smith said.

Smith also said that it shouldn't be an issue for SPD to turn over these records to protestors, because SPD already has access to the records in question.

"It's pretty easy for them to produce them. … When they do arrests and refer cases, what they are doing is they are putting together a report and they submit [it] to the prosecutor's office. So, they already have a chunk of that stuff completed, and they literally just have to email it [as] responses to the records [requests]," Smith said.

SPD media's Sgt. Lauren Truscott said in an email to the Emerald that superforms, which are among some of the information the protestors are requesting, are available as public record with the King County Jail. These forms include the arresting officers' names and a concise statement of allegations.

King County Jail communications specialist Noah Haglund said that superforms and other related jail records are kept confidential with exceptions listed here. He said that if people want to get ahold of their own superforms, they should send an email to records.dajd@kingcounty.gov or call the jail's records office at 206-477-5130. He said jail staff will ask for their identification to verify their identity.

When asked if SPD could prioritize certain requests, such as those outlined in this article, SPD Deputy Police Counsel Cherie Getchell said that "[t]he Public Records Act states that agencies shall not distinguish amongst requestors, which means that we cannot prioritize any one individual's public disclosure request over another requestor."

Aside from their personal accounts of what happened to them, based on memory, and the superform data available at King County Jail, protestors still lack a substantial amount of tangible proof or information for use in court. This dearth of information is apparent in the protestors' public records requests. Riggs, who was arrested earlier than Cooney on July 25, sent the Emerald several emails showing her initial records request and subsequent communications with the City of Seattle's Public Records Request Center. Riggs' original request is sparse: not only does she not know her incident number, which would help in tracking down her arrest record, but she also doesn't know who are her "investigating officers" — the officers who arrested her.

Cooney's records request contains only a little more information, in that she knows her incident number. But like Riggs, she doesn't know who the officers are who arrested her. Neither woman knew they needed to go through King County Jail to get their superform data, which would have this information.

To Smith and many of her clients, this lack of transparency plays a role in their concerns about the Office of Police Accountability (OPA), which Smith contends hasn't done its job and continues to fail the public. She said OPA is nothing more than a "placating position," and neither it nor SPD itself will keep the police department in check. Even if the OPA does find an officer in violation, she said, it's because that officer's conduct was "so egregious" that OPA couldn't simply send the officer on their way with just a slap on the wrist.

"[OPA]'s inability to manage the situation, their … slow response rate, and the ongoing community brutality — it's just like the ongoing conversation about reform is just empty," Smith said, going on to list the numerous attempts at police reform in Seattle and Washington State, like 2012's consent decree, 2018's Initiative 940, and the ongoing protest movements.

The OPA said on its website that it has been contacted more than 18,000 times about SPD's response to recent protests alone. So far, these 18,000 complaints have initiated just 34 investigations, the status of which OPA updates on a dedicated page on its website. As of this writing, the OPA has completed 216 cases in 2020. With the exception of a handful of these cases, most resulted in No Allegations Sustained, which, according to the OPA website, means "[t]he evidence indicates the alleged policy violation did not occur as reported or did not occur at all."

Smith said that even if OPA eventually finds the officers in question at fault and they are removed from the force — which she doesn't see as even remotely likely — if these officers are allowed to continue working in the interim, what does that mean for the average person on the street?

"It shows the danger to the community who aren't protesting — just on the street, when there aren't a ton of witnesses, there's not a bunch of people with cell phone video, and you aren't white and well-off," Smith said. "When people who are white and well-off are being treated this way, and can't get access or the cops are brutalizing them — this is going to have a disparate impact on [Black, Indigenous, and people of color] communities who are not going to have a bunch of witnesses, or people in a position to advocate for them."

The inability for protesters to get access to their arrest records, associated documents, or any other recorded material relating to their arrests is not the only problem they're facing. Many are still trying to collect their belongings from SPD's Evidence Unit more than two weeks after the July 25 protest at which they were arrested. Smith said protestors have been run through a gamut of people at SPD just to get to the Evidence Unit and figure out where they need to go and what they need to do to get their belongings back, a task made more difficult by the evidence room's reduced staffing hours, due to the novel coronavirus pandemic.

Even the handful of people who have gotten their belongings back have been dismayed, Smith said. She said that a member of the media whom her firm is representing, but who wanted to remain nameless, noted that someone had rifled through their belongings and had returned the reporter's SD cards with corrupted or missing files.

Truscott said that "[i]t is unfortunate if people's property is damaged upon arrest or while they are in police custody. People's property should be housed at the SPD Evidence Unit, and they should be able to pick it up with an appointment."

Cooney said in an email to the Emerald that the process of collecting any information from SPD is "almost impossible and never straightforward," and that she's still trying to get all her belongings.

"My boyfriend and I got a notarized form so he could pick up my belongings for me because I was too afraid to go. What I got back is still covered in pepper spray," she said. "My backpack has had the straps cut off. I did not get my cloth face mask or goggles back after an officer ripped them off me."

Truscott said that Cooney's arrest report claims that Cooney was "sitting in front of a bike line, refusing to move," so an officer "pulled the person by their backpack out of the way of the bike line that was advancing forward." Truscott asked if it's possible the backpack was damaged then.

Cooney said that she didn't refuse to move, and that it's possible the backpack was damaged then. However, she said it's missing the straps entirely — they aren't just ripped and hanging off the bag. A video of Cooney's arrest by the Emerald's Liz Turnbull appears to show the bag's straps intact, despite officers using the backpack to drag Cooney across the ground.

Cooney also noted that even though she got her phone back, several videos she had taken of officers during the protest were corrupted.

Riggs said that she understands SPD's media unit is understaffed — one of the messages she received said that it has fewer than 10 people working on more than 2,100 media requests — but that the media unit for a major metropolitan police department should not be so small. To Riggs, the entire process feels like a frustrating jumble, "almost intentionally so."

"I worry that a lot of the video evidence that I also requested is not going to be available or maintained until the supposed completion date for my records. I would love to have the body camera footage," Riggs said. "I would love to have the footage from when we were in the holding cells, when we were being transported, all of that — just so I have that. And I am afraid it's going to be gone, by the time they actually get the records to me."

Truscott said body-worn camera footage evidence has varying lifespans, depending on the statute of limitation of the crime with which an individual is charged, as well as on the status of appeals of a particular case. However, it was impossible for the Emerald to offer Truscott specifics, because Riggs did not know with what she was being charged at the time of this writing.

Truscott did not specify the minimum amount of time body-worn camera footage is kept, but said the maximum amount of time is indefinite for crimes like homicide. She directed the Emerald to look up the statute of limitations to "get an idea of what some of those lifespans are."

After digging up this SPD training manual, which points to RCW code 9A.04.080, it appears that the minimum amount of time body-worn camera evidence is retained is one year.

The Emerald has reached out to OPA for comment and will update this article if the office responds.

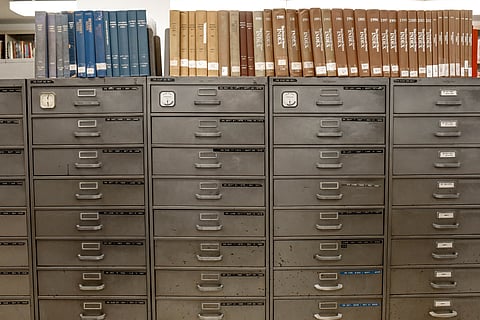

Featured image from Pexels.

Help keep BIPOC-led, community-powered journalism free — become a Rainmaker today.