OPINION: Love and Accountability

by Meg McGuire

(Adapted from a sermon delivered to the First Unitarian Universalist Society of San Francisco, February 28, 2021.)

What does the word "accountability" evoke for you?

Accountability feels to me like one of those words that we hear all the time but might struggle to define. Like one of those words that's used so much that its meaning starts to get obscured. One those words that sees a lot of traction, but very little precision or careful unpacking … and one of those words that may carry a connotation that doesn't have much to do with its actual meaning — at least not the way I understand it. What does the word accountability evoke for you?

These days,- faced with harm and wrong-doing- on so many levels of our public life, it's a common question.

"Where is the accountability?"

"We need to hold them, her, him, accountable for their actions."

Often, these calls for accountability articulate something important. The desire for justice in the face of negligence, violence, or wanton disregard for others.

The thirst for this thing we call accountability can feel righteous and necessary in service of truth and reconciliation.

But, at the same time, the word accountability takes on a sort of terrifying, even bullying quality. The language of accountability starts to feel more like a weapon, or a threat. Something that someone does to someone else.

Something that can be done to you.

While we might hunger for accountability on the level of politics or when it is happening to someone else, when accountability comes up in our personal lives it can feel a lot less welcome.

Because, for many of us, we've come to conflate accountability with punishment.

Indeed, the two have gotten so jumbled up together that it can be hard to parse them apart. But it matters that we do.

In her writing about the costs of mass incarceration, Danielle Sered, founder of the organization Common Justice, argues that the criminal justice system, what can seem like the logical vehicle for accountability, is actually diametrically opposed to it; a sort of "kryptonite to accountability," she says. There are, of course, the moments, many of them in our recent collective memory, where some people, even with seeming clarity of their culpability, never see the inside of a courtroom or the seemingly just verdict. But even taking the cases where the justice system does seem to be working as intended, Sered argues, it remains a poor vehicle for accountability.

From the trial, where pleading not guilty, regardless of one's relationship to the offense, is strategic and even encouraged. And certainly in jail or prison, which severs people from community, and has morphed, as activist and philosopher Angela Davis has long reminded us, from a means of rehabilitation; to a system centered on punishment as an end in and of itself.

"For all the ravages of prison," Sered writes, "it insulates people from what they've done" though cries for accountability persist, practically, punishment has displaced it.

The impact of this conflation is hard to fully comprehend, Sered tells us. But we have an opportunity, she says, "to reverse that displacement, to reclaim what we have given up and what has been taken from us, and to begin the work of building the accountability based culture we all deserve."

Sered and her organization are part of the world of transformative justice, a field of study and practice that considers community-based alternatives to incarceration and community-based ways to respond to harm.

Transformative justice holds a vision, one of a world that can respond to harm in ways that honor the humanity of all involved, responses that can sustain — even deepen — community all the way through, and get to the root of structural change required to prevent harm in the future.

It's an example of moral imagination of the most audacious kind. The kind of vision that can be hard to even wrap our heads around so long have we been steeped in another vision of "justice." To an outsider, the vision of transformative justice could seem naive, out of touch with the realities of harm that people do to one another.

Quite the opposite though, transformative justice begins from the assumption that we will hurt one another. Shaped as we are by the layers structural inequity, and harms that are quite literally generational. Harm will happen. We will disappoint each other. We will hurt each other. We will mess up, in ways both big and small.

Yet, the path forward isn't to start with the biggest, most intractable harms, at least not by itself. For change to happen on the collective scale change is required on every level. As transformative justice visionary Mia Mingus asks, "If we cannot handle the small things between us, how will we handle the big things?" What we practice on the small scale can build our capacity for the bigger structural work, and vice versa. The patterns around accountability and punishment that shape our politics, our institutions — these play out inside each of us, too.

It demands interrogation, then. When we talk about accountability in our intimate relationships, in communities like this one, what do we mean?

I have a hunch that most of us have experienced or witnessed punishment masquerading as accountability. Attempts at holding to account that, deliberately or not, use shame as a tool. Attempts that rush past the relational component of this work straight to fissure, expulsion, or exile, what some people describe as "canceling." To be sure, there can be situations where this can be a necessary response, for survivors and others.

And, we know that there are plenty of situations when the fear and shame that these punitive interpretations of accountability evoke — not just in the person being taken to task, but to witnesses, too — shuts down learning, shuts down change, and ultimately, shuts down accountability.

It is no wonder then, that accountability gets a bad rap. It is, I think, fear of being cancelled, cut off from community that is behind our collective aversion to this deeply necessary work, avoidance that consequently creates a culture where true accountability is hard to find.

—

Maybe it doesn't have to be that way. Mia Mingus, an educator, writer, and visionary, in the fields of transformative justice and disability justice, offers an alternative vision, a dream, of how we might be together differently.

"What if accountability wasn't scary?" she writes: "It will never be easy or comfortable, but what if it wasn't scary? What if our own accountability wasn't something we ran from, but something we ran towards and desired, appreciated, held as sacred?

What if we cherished opportunities to take accountability as precious opportunities to practice liberation?

To practice love?

To practice being the kinds of people … we want to be?"

What if we trusted accountability was done with love and knew that we too could name and be heard in what hurt, what went wrong — when it happens to us — and to heal, rather than carry our hurt around, or wall ourselves off in anger or pain. What if?!

What if?!

What if we considered accountability to be a kind of love — a love of self — and love of others?

One of the big observations that Mingus makes is that accountability must be consensual. It cannot be forced because it requires change, and change, ultimately, is a choice — a choice that each of us makes for ourselves. So, for instance, she encourages rather than thinking about holding others accountable, we consider first how to be accountable ourselves. Learning to be accountable is a skill, Mingus says, an art, and a craft,. It is a muscle that each of us can start developing, so that it's stronger when inevitably we need it.

But that doesn't mean it's something we do alone. Writing on the subject, Black liberation activist and author Malkia Devich-Cyril asserts that while accountability isn't something that we hold each other to, "it is something we can help each other be." It is something we practice together.

Does that sound hard? Complicated? Difficult to know where we even start?

It might be… but each one of us, I think, is already practicing some version of accountability. Each one of us, I suspect, has a relationship, or several, where we practice accountability without thinking twice, where it might not always be easy, but it isn't scary. You make sure your kid gets a healthy dinner; your dog gets their vaccines; your mother gets a card and lunch out on her birthday; your spouse is treated with respect and honesty so the partnership remains strong; that you honor the professional ethics you swore an oath to. And if your kid, your mother, your partner, your colleague, tells you you've hurt them, you pause, listen, and change.

Accountability is there in the showing up. In doing what you say you're going to do. And owning up when you don't. As Daniel Jackoway says, accountability is "reminding [each other] when we step out of bounds, and even more importantly, responding to those reminders with grace, humility, and genuine intent to change." Even when it wasn't your intent to hurt, as Daniel modeled so beautifully.

Essentially, accountability is an affirmation of relationship. As we deepen into the practice, it widens the circle of concern, bringing in all the relationships that knit our lives together into a powerful, regular reminder of our fundamental interdependence. It is an affirmation of everyone's humanity, an affirmation of the truth of each one of our inherent dignity, whatever happens between us.

For me, accountability is about choosing to stay in relationship, even when things are hard, and work with the strength of the relationship in mind, always. It involves acknowledging that harm has happened — or will, for sure — then choosing the relationship and healing above all else.

I think we need to tell each other these stories.

Doing the work and talking with each other honestly about it might help us to grow into this practice, in putting love over punishment and healing over retribution, knowing that each expression is not a solitary action, but as Mia Mingus suggests, "an intentional drop in an ever-growing river of healing, care, and repair," a drop that has potential "to nourish, comfort and build back trust on a large scale, carving new paths of hope and faith through mountains of fear and unacknowledged pain for generations."

Like drops of water that can gradually carve through rock, we start small, in the workshop of our daily lives, knowing that all of us at some point will be on both sides of harm. What if we start by holding ourselves accountable, not with shame or self-punishment but holding honesty and love and relationship as we step toward the harm and the repair.

Start, as we will this year, holding ourselves as a community accountable for prioritizing healing from the harm of racism and oppression.

Do so by honoring the gift of feedback that we've been given by People of Color in our community, in our denomination, and in our country, that things need to change.

Meet that gift with the gift of showing up, moving toward accountability, knowing that it is an expression of our covenant with one another, exercising power in the opposite direction of the harm.

May we turn away from fear and turn toward learning, toward dreams that require some more personal and interpersonal work for us to plant them firmly in our communities and our world.

May we remember that accountability is the work of love.

Meg McGuire is a ministerial intern at First Unitarian Universalist Society of San Francisco. A lifelong Unitarian Universalist, Meg has long been guided by her faith's affirmation of the essentiality of all people and commitment to more fully realize our fundamental interdependence with all of life. She first responded to this call as a labor organizer.

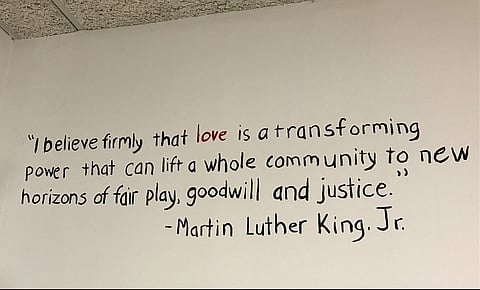

The featured image is attributed to anokarina under a Creative Commons 2.0 license.

Before you move on to the next story …

The South Seattle Emerald™ is brought to you by Rainmakers. Rainmakers give recurring gifts at any amount. With around 1,000 Rainmakers, the Emerald™ is truly community-driven local media. Help us keep BIPOC-led media free and accessible.

If just half of our readers signed up to give $6 a month, we wouldn't have to fundraise for the rest of the year. Small amounts make a difference.

We cannot do this work without you. Become a Rainmaker today!

No Paywalls. No Billionaires. Just Us.

We're raising funds to hire our first-ever full-time reporter and grow our capacity to cover the South End. Support community-powered journalism — donate today.