VOICES: Taking Off Our Masks to Breathe

by Sophia Malik

My stethoscope lingered on the back of my patient. I realized I was steadying my breath more than listening to hers. The fabric she wore to cover her hair had the same feel as the fabric my mother wore during my childhood. It's not a Walmart cotton. It's a cotton you can only buy back home: soft and cozy, typically worn by soft and cozy aunties, carrying a scent of food freshly cooked by the wearer.

After becoming a mother myself, I became aware that these fabrics, the sounds of the languages spoken by those wearing them, the traditions and the people wearing them, are fading into memory. The reasons for these losses vary from the natural passing of time and health to the unnatural but common brutality of the systems we live within. I wondered how I could use the pieces of the past that were life-giving to recreate a nourishing present for my own children.

The last few years of creating an ecosystem for my kids that reflected the world I hope for them to experience became an open window for me in a world of closed doors. Existing in white-led institutions in Seattle can mean having to describe myself and my needs through someone else's lens, a someone else who may find bothersome my desire to exist as I am.

Equity conversations are so important, but the reality of sitting in these conversations often feels like an act of justifying my worth. We need to know what we are against, but if we only focus on being against something, we begin to be defined by that thing and maybe even motivated by it. We can survive in spite of that thing, but we can only thrive if we figure out what things we are for, what we want to grow, who we want to be and put our energies and innate power into creating those things.

Even though I was born in the United States, my strategies were not very different from those my mother used to survive as a new immigrant. She cultivated community in the new hometowns she found herself in. Together, they exchanged food, advice, help for each other's kids and made space for grief and joy. We never felt like we had, or were, less because we were abundant in the resource of relationships.

I made similar choices with my daughter. We attended Friday prayers at the masjid so she could see how we stand shoulder to shoulder in a kinship that goes beyond outward appearance. We kept our home open so she could see how through feeding others we sustain ourselves. We traveled so she could experience the love of her elders, know the sound of her native language, and understand who she is outside of a nuclear family. We gave thanks for the endless generosity and presence of the people around us.

When the global pandemic started, I worried about having PPE and hand sanitizer, but I was also very worried about losing the spaces and people of our ecosystem. We lost restaurants, schools, studios, libraries, and festivals where we were free to be and create. We tried to replace them with a virtual reality. For those of us whose physical safety is not prioritized in this society, the physical spaces we had were a world within a world where we were safe, a place to take off our many masks, breathe, and hold each other.

The time in isolation has also revealed to us what habits of our communities or relationships were not serving us. We have learned to ask for the things we always deserved and say no to things we realized we never wanted. We put words to feelings we have carried, and we saw truths we will not unsee, no matter how many distractions will be added back into our lives if and when the pandemic is controlled. And we expanded our capacity to find a safe space inside ourselves.

So many of us are trying so hard to hang on to our ancient knowledge of what we know the new world should be. Before, I was driven by the memories of my aunties. Now, I also have to be driven by the memories of the aunty I was becoming before the pandemic. I will continue to practice the traditions that I can and carry the wisdom of the ones I cannot due to the current physical distancing restrictions. My daughter, one day, will remember the feel of a cloth mask snug across her face. I hope she also remembers how to open her home, give and receive from community, and, no matter the challenge or restrictions, she will move in a way aligned with who she is and where she comes from.

Sophia Malik is a family medicine physician and lives in South Seattle.

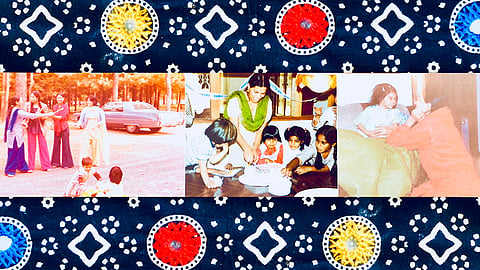

📸 Featured Image: "A Mother's Love As Resistance" by Sophia Malik.

Before you move on to the next story …

The South Seattle Emerald™ is brought to you by Rainmakers. Rainmakers give recurring gifts at any amount. With around 1,000 Rainmakers, the Emerald™ is truly community-driven local media. Help us keep BIPOC-led media free and accessible.

If just half of our readers signed up to give $6 a month, we wouldn't have to fundraise for the rest of the year. Small amounts make a difference.

We cannot do this work without you. Become a Rainmaker today!

No Paywalls. No Billionaires. Just Us.

We're raising funds to hire our first-ever full-time reporter and grow our capacity to cover the South End. Support community-powered journalism — donate today.