OPINION | Magnolia Fights for Last Minute Switch Without Acknowledging Its Own Racist Past

by NiRae Petty

Historically, (since 1787, to be exact), white and wealthy communities have thrived at the involuntary expense of Black, Brown, and Indigenous People of Color and the working class — in the name of "compromise." This year, the quote, "History doesn't repeat itself — but it does rhyme," couldn't have been more timely.

Next month, the Seattle Redistricting Commission will finalize our new city council districts for the next decade. When used fairly, redistricting could achieve more equitable representation and funding by redrawing voting districts to reflect population changes and growing diversity. But there's a catch: This process usually falls short when determining which neighborhoods should compromise by being split and have diminished voting power.

The Redistricting Justice for Seattle (RJS) coalition argues that any compromise made should be to preserve and increase Black, Brown, and Indigenous and low-income and renter neighborhoods' representation by keeping them together. However, some residents of Magnolia, a majority white and wealthy neighborhood, have protested against these "special interests."

In the commission's first map proposal, Magnolia was split between two districts to keep areas of Fremont, a working-class, renter-heavy neighborhood, together. In response, Magnolia residents had expressed fears about the change affecting their neighborhood's "public assets." Their community safety might be jeopardized from lack of infrastructure development and maintenance. Schools, parks, and libraries might be deprioritized for renovations, failing to give community members effective access and resources for workforce development or higher education.

In other words, they're afraid of the very things that result from the disenfranchisement of BIPOC and low-income communities.

In her testimony, Jude Ahmed, civic engagement organizer with the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle, argues that "these fears have already been realized by the Communities of Color who were left out of the creation of the original city council districts." In 2013, a wealthy North Seattle resident, Faye Garneau, bankrolled a charter amendment campaign for single-member districts. This potentially could have helped underserved communities. Instead, Garneau stated she "doesn't believe in the racial stuff."

Undoubtedly, the first map submitted and used kept majority-white neighborhoods together while splitting up Communities of Color and low-income neighborhoods like Yesler Terrace and Fremont.

This year, in the Magnolia Chamber of Commerce's argument against the split of their "historically significant" neighborhood, they claim that "every community in Seattle benefits" from their political presence. This statement fails to acknowledge Magnolia's most significant historical impacts on Seattle, which decreased the livability, property values, and tax revenue of BIPOC and low-income communities around them.

For decades, neighborhoods in Seattle had racially restrictive covenants and used zoning to exclude BIPOC residents from their area. And, as Jazzlynn Noni Woods, senior research associate for UW's Racial Restrictive Covenant Project, states, "Though racial covenants and redlining were stricken by federal laws, the effects are still evident today."

She continued, "… low-income communities were exploited, leading to skyrocketing rent prices and property values, ending in displacement. It's no coincidence that these areas remain some of the whitest, wealthiest neighborhoods in Seattle."

It is not a coincidence that maps used to determine political power are another tool used to continue this exploitation.

Ultimately, a fair compromise is difficult in a society thriving off of white supremacy. Without awareness or a strong voice in the process, neighborhoods like Fremont and Yesler Terrace will continue to risk being on the chopping block. Adding on, Andrew Hong, co-lead of Redistricting Justice for Seattle, shares that the issues in our single-member districts "prevent BIPOC representation beyond that 1 majority-BIPOC district." However, the maps submitted by RJS are proven to divide the least number of Seattle communities and emphasize renter and low-income voting power. Fortunately, due to strong organizing, the Commission has proposed a map that mostly reflects these values, but one commissioner, Greg Nickels, still argues against it.

We need more voices that center communities in the redistricting process over the special interests of white and wealthy neighborhoods. Testify to tell the Commission to pass the newly amended map by Nov. 2, before their final vote for our new district lines.

The South Seattle Emerald is committed to holding space for a variety of viewpoints within our community, with the understanding that differing perspectives do not negate mutual respect amongst community members.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the contributors on this website do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints of the Emerald or official policies of the Emerald.

NiRae Petty is the advocacy program manager at the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle, a nonprofit organization that provides direct services and advocacy for Black and other underserved communities in the Greater Seattle area.

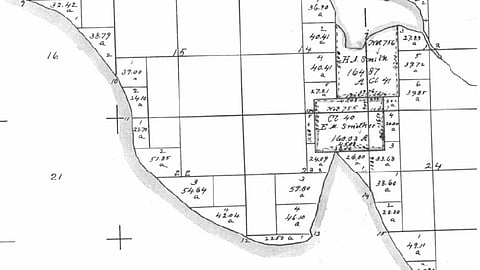

Featured Image: Part of 1863 (United States) Government Land Office map showing what is now Interbay and most of Magnolia in Seattle Washington. Salmon Bay is to the north; Smith Cove juts in from the south. Note the claims by H. A. Smith and E. M. Smither. Smith eventually came to own Smither's claim. The map shows the natural shape of the land before the dredging of a canal to the northeast and the filling of much of the cove to the south. Map is attributed to BOLA Architecture + Planning & Northeast Archealogical Associates, Inc., Port of Seattle North Bay Project DDEIS: Historic and Cultural Resources (under the public domain in the United States).

Before you move on to the next story …

The South Seattle Emerald™ is brought to you by Rainmakers. Rainmakers give recurring gifts at any amount. With around 1,000 Rainmakers, the Emerald™ is truly community-driven local media. Help us keep BIPOC-led media free and accessible.

If just half of our readers signed up to give $6 a month, we wouldn't have to fundraise for the rest of the year. Small amounts make a difference.

We cannot do this work without you. Become a Rainmaker today!

Help keep BIPOC-led, community-powered journalism free — become a Rainmaker today.