'Our Community Has a Hole': Family and Friends Mourn the Loss of Mahamadou Kabba, Man Slain in Renton Shooting

by Lauryn Bray

At 1 p.m. on Jan. 12, beloved family man and father of five, Muslim community leader, and ride-share driver Mahamadou Kabba, 35, was shot in Renton during a string of shootings that later killed him and seriously wounded two other men. Kabba and Sami G. Mebrahtu, 30, were both shot multiple times and subsequently taken to the Harborview Medical Center, where they both underwent surgery. A third victim, Leonard Walker, sustained gunshot wounds to his right thigh, right hip, left hip, and right wrist, but did not require extensive treatment. The shooter, Mamadou Aliou "Lee" Diallo, 32, was arrested in Tacoma and booked into the King County Correctional Facility at 2:40 p.m. With these acts of violence, Diallo had ripped apart the lives of several unsuspecting families.

"Mahamadou is a great person. Mahamadou is not violent. I've never seen Mahamadou get angry, I've never seen him upset. He'll be sad if something happens to somebody — he feels it as if it is his. Mahamadou is that kind of person," said Imam Bayo, Gambian Muslim community leader and a close personal friend of Kabba, in an interview with the Emerald.

Kabba's loved ones spoke about him mostly in present tense. Their struggle to maintain a consistent grammatical tense shows how unfathomable Kabba's death is.

"He's very supportive, very caring, very giving. He was a family man. He would drop whatever he's got going on if you ask for help, he's always there," said Kabba's stepdaughter, Entisar Ibrahim.

Kabba was shot near the intersection of Rainier Avenue South and South Tobin Street — according to friends and family, he was coming out of the nearby mosque.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, homicides in King County have risen, but they are still not as high as they were in the early 1990s. "The past two years have seen 52 and 53 homicides in Seattle, respectively, while 1995 saw 48. However, 1994 and 1993 saw 73 and 74 homicides in Seattle, respectively," said Kerry Harwin, director of communications for Drivers Union, an organization aimed at protecting the rights of professional drivers. "While the dominant media narrative certainly would have us believe that we're seeing record-high gun crime, the data doesn't quite back that up." Harwin's theory for the recent spike in gun violence? The COVID-19 pandemic itself.

"I'd point to the impacts of the pandemic, both in terms of the increase in general human poverty and misery and a COVID-era spike in gun purchases, as the likely cause of the higher gun violence today. For instance, Seattle saw 31 homicides the year before the pandemic, in 2019, with the current spike beginning only after the onset of COVID," explained Harwin.

Crime data from King County also shows that homicide rates have increased since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to data from the King County Police Department published in an article from KIRO 7, there were 69 "shooting murders" in 2020. The article also states that by the time it was published in October 2021, there had been "73 people shot and killed in King County."

For the family and friends of Kabba, though, explanations are insufficient. "Mahamadou has his kids, his wife, and other siblings in the family that all depend on him. He provides for everyone, and all of a sudden he gets murdered in this situation," said Bayo. "So now the problem is the wife and the kids — how are they going to continue to live as they are supposed to, as if he was here, with no one to support them?"

Kabba has five children across three continents: the United States, Africa, and in Europe — and he was the primary breadwinner for all of them. Since his brother's passing, Kabba had also been financially responsible for his two wives and their children, in addition to his own wife, Khadija Mohamed.

Police found Kabba's car riddled with bullets — after being shot, he stumbled out of his car and into a nearby business, where the owner recognized him and called the police. Kabba was taken to the hospital, where he died two weeks later.

"I thought he was going to make it," said Ibrahim. "I was sure, because he was stable. The vitals were good — he was on blood pressure medication and he came off of it. The doctors were even thinking of taking him off the oxygen, so he was getting better."

While Kabba was in the hospital, Ibrahim was thinking about ways to facilitate her stepfather's healing. "I was thinking about recovery. I wasn't thinking about burying him," she said. "I was thinking about how we were going to help him, because it was going to be a long road to recovery, if he had made it."

However, unlike Ibrahim, Kabba's wife knew he wasn't going to make it. "For me, it was out of nowhere," Ibrahim said. "My mom was different. Maybe she had more experience with death, I don't know. She was out of the country. She came four days after [the shooting]. From the day she saw him, she had a feeling he was not going to make it. I was like, 'No, I don't want to hear it. You're always a downer.' I was mad at her."

Ibrahim says her hope that Kabba would live was exacerbated by a dream her husband had. "My husband was telling me this: Five days before [Mahamadou] passed, he said he saw Mahamadou in a dream," she explained. In the dream, "He was hugging me and he tried to pick me up, and I was saying to him, 'Oh no, don't pick me up, your stitches are still fresh,' and he was like, 'No, I'm better now.'"

Ibrahim continued, "When he told me [about] the dream, I felt he was going to get better. But my mom — she interprets dreams — so when she heard that, she looked sad."

According to Ibrahim and Mohamed, Mahamadou's recovery took a turn for the worse after the doctors tried to feed him. "Because he had lost most of his bowels, when they fed him through the entry tube, instead of the food going inside his bowels, it went outside and caused an infection," explained Ibrahim.

The doctors started feeding Kabba on Thursday, and by Tuesday, he was gone. This fact is especially difficult for Bayo to come to terms with, as the weight of responsibility for his community rests heavier on his shoulders without Kabba.

"Our community has a hole. Where he was, there is now a gap. We have nobody who can fill that gap," Bayo explained. "In our meetings, he would always be the last person to talk. After we all talk and everyone has shared their ideas, he would say, 'My suggestion would be if we do such and such, that would really help the community.' He would always talk about what would be beneficial for the community."

Kabba's family says he never missed an opportunity to help someone. "He had a next-door neighbor who is an elderly Vietnamese lady. She doesn't speak English — not a word — but he found a way to communicate with her. He would ask her if she needed help, and he would. He was the one who would bring her groceries. Her son lives in Texas. [Her son] would Zelle [Kabba] the money and he would go buy her groceries," said Ibrahim.

According to Ibrahim, when Kabba wasn't helping people outside the home, he was either at the mosque or working to support the family. As a ride-share driver, Kabba would work at any hour, only stopping during his shifts to pray at the closest mosque. The day he was shot, Kabba was on his way from praying dhuhr.

Almost two hours after Kabba was shot, Diallo was arrested in Tacoma after a SeaTac police sergeant spotted Diallo's vehicle traveling southbound on I-5. Police were able to identify Diallo's vehicle after viewing surveillance footage from Ezell's Famous Chicken. The sergeant arrested Diallo at a traffic stop, and, according to court documents, he was found with a Walther-brand pistol box in the front passenger seat and at least one fired bullet casing.

After his arrest, Diallo was taken to the King County Correctional Facility and charged with three counts of assault. However, since Kabba's death, one charge has been updated to first-degree murder. Diallo denied shooting anyone and pleaded not guilty. He remains in jail, held on a $3 million bond.

In those same documents, police stated that Diallo said several times that he "does not like Black people" and does not spend time with them because "they are always killing each other." Kabba, Mebrahtu, and Walker — as well as a third victim who was pushed to the ground inside the Safeway located at 200 S. 3rd St. — are all Black men. Diallo is Black as well.

According to Ibrahim, police were trying to make a connection between Diallo and the men he shot. "Police were trying to make it seem like they knew each other — which they don't — just because they're both West African," said Ibrahim. "He shot three people, and they were all from different countries." Kabba is from Gambia, Mebrahtu is from Eritrea, and Walker is African American.

"I suspect that especially when they see violence between two West Africans, they don't look as hard," said Drivers Union's Harwin. Kabba was involved in the early stages of the organization's activism, and since his death, Drivers Union has worked closely with Kabba's family.

Not only will Kabba's death leave a long-lasting impact on everyone who knew him and all who will never get the chance to meet him, but it also highlights the dangers of being a ride-share driver.

A report from the San Francisco Chronicle analyzed data on injuries and fatalities from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Statistics from the report, which is hidden behind a paywall, were published in an article from Risk & Insurance. According to the article, the fatal injury rate for Uber and Lyft drivers is 14.6 out of every 100,000 workers, making 80.5% of jobs safer than driving for a ride-share service. Additionally, Uber and Lyft have fatality rates that are 1.1 and 1.6 times the fatality rates for police officers and firefighters.

While Kabba was not shot by a passenger, statistics show that his profession made him a bigger target — there is inherent danger in working in a profession that requires employees to constantly be outside and interacting with strangers. Additionally, the lack of routine and the absence of protection that comes with working in a building can exacerbate the consequences of a potentially dangerous event.

Since Kabba's death, his wife has organized a GoFundMe to support the family. If you are interested in helping the family continue to cope with this tragedy, you can donate here.

Lauryn Bray is a writer and reporter for the South Seattle Emerald. She has a degree in English with a concentration in creative writing from CUNY Hunter College. She is from Sacramento, California, and has been living in King County since June 2022.

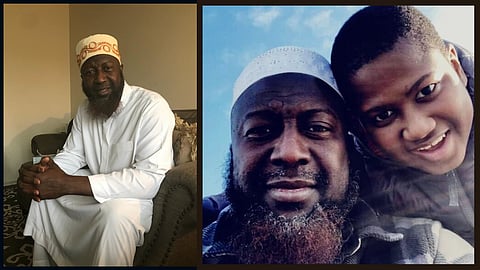

Featured Image: Left: Mahamadou Kabba at home the day of Eid 2022. Right: Kabba at Alki Beach with his son, also named Mahamadou. (Photos courtesy of Entisar Ibrahim.)

Before you move on to the next story …

The South Seattle Emerald™ is brought to you by Rainmakers. Rainmakers give recurring gifts at any amount. With around 1,000 Rainmakers, the Emerald™ is truly community-driven local media. Help us keep BIPOC-led media free and accessible.

If just half of our readers signed up to give $6 a month, we wouldn't have to fundraise for the rest of the year. Small amounts make a difference.

We cannot do this work without you. Become a Rainmaker today!

No Paywalls. No Billionaires. Just Us.

We're raising funds to hire our first-ever full-time reporter and grow our capacity to cover the South End. Support community-powered journalism — donate today.