COLUMN | From Seattle to Minneapolis: Grief Travels, and So Does Solidarity

A toddler in the snow is blissfully oblivious of how death stains the world around her. She doesn't notice the candles and the tears, and she doesn't register the vigilors' prayer-lines or the bite of the cold Minneapolis air. She also doesn't register that Alex Pretti was murdered just feet from where she forms snowballs. The innocence of play obstructs grief, and for a moment, I envy her: to not bear the weight of the last 72 hours, three vigils for four lives lost, and three reminders that life here in the United States is fragile in the rawest, most unforgiving ways.

I am here because our nation is watching, our city is anxious, and South Seattle is hurting.

Back home, two young men were killed in Rainier Beach, leaving a community to make sense of the senseless gun violence that took their lives. I'd left their vigil less than 24 hours ago to be here in Minneapolis, standing at a makeshift memorial site erected where Alex Pretti was killed by ICE agents a week ago. The next day, I'll travel to another memorial site in the residential neighborhood where Renée Good was fatally shot by a federal agent on Jan. 7. Both were U.S. citizens, and both of their deaths have ignited a series of nationwide protests.

Seattle Is Next?

Seattle is uneasy. Not yet under siege, not yet the site of nightly headlines, but alert in the way a family becomes alert when they hear sirens in the distance. We have watched federal immigration enforcement swell in other cities. We have watched neighbors detained in daylight. We have watched two civilians in Minneapolis be murdered in encounters that began with ordinary people refusing to look away.

Speaking to a group of us who'd made the trip to Minneapolis from the Emerald City, Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison warned that the administration's tactics won't stop in his state, arguing that cities like Seattle could be next in line for aggressive federal intervention. He cautioned that the Trump administration's goal is to build a kind of federal "Praetorian Guard," forces untethered from local accountability and responsive to a single chain of command.

So, I went to bear witness to who they have become, to perhaps inform who we in Seattle just might be, and to confront the question I carry with equal parts hope and dread: whether this moment is truly different from the long ledger of deaths that once stirred a nation's conscience, only to be folded back into the familiar quiet of forgetting.

Two Lives, One Pattern

On the morning of Jan. 7, after dropping her 6-year-old son at school, Good, a 37-year-old remembered for her warmth, found herself on a street she had lived on for years — not a battlefield but her own neighborhood. She and others were alerting neighbors to the presence of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) vehicles with honks, whistles, and calls, a simple civic instinct to protect one another.

Moments later, as she pulled away, an agent raised his weapon and fired several shots into her car. The memorial in her neighborhood, an outpouring of love, marks the sudden end of a life that was ordinary in the most beautiful ways: loving, connected, and deeply rooted in community.

Pretti was an ICU nurse, a veteran caregiver at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center. On Jan. 24, he was filming agents with his phone and helping someone else, and he was shot while he attempted to stand between an agent and a woman the officer had pushed. Video shows him holding only a phone, pepper-sprayed and wrestled by federal officers before shots were fired. Along with Good's, his death was ruled a homicide.

Good and Pretti weren't anomalies. They were neighbors caught in a moment when the machinery of the state, masked, armed, and emboldened, rolled into Minneapolis with little concern for the bodies it would disrupt. In recent months, residents formed informal networks to watch federal agents, not to provoke violence, but to bear witness to the human toll of an enforcement surge steeped in fear and racism.

For the first time, many in this country are witnessing a justice system indifferent to their pain. A House committee's report released last week calls out a cover-up by the White House and the Department of Homeland Security in both shootings. And in Washington, Good's own brothers demanded accountability from lawmakers.

While administration defenders claim a "softer touch" might be possible, the reality on the ground remains raw. More than 2,000 federal agents are still stationed in Minnesota even after a "withdrawal" of 700 personnel was announced by Tom Homan, the Trump administration's "border czar."

All that and more roils through my mind as I stand with hundreds at Pretti's memorial site, still struggling to give shape to the unfathomable.

What Grief Built

At the vigil for Pretti, I spotted a white man wearing a shirt that read "Stop Killing Us." It stopped me in my tracks, not because the message was new, but because of who was finally carrying it. For generations, Black people have said those exact words in a thousand different ways — in protests and desperate pleas caught on cellphone cameras — and we've been met with denial, distortion, or silence. Standing there in Minneapolis, in the long shadow of where George Floyd called out for his mother, I felt a tangle of grief and recognition.

A grief that so often requires spectacle, blood, and viral video for the warning to be heard. Recognition that maybe, just maybe, the truth Black communities have been living with all along is cracking through the walls of disbelief. The shirt was not absolution. It did not erase the years America refused to listen. But it was evidence that the testimony is no longer containable — that the cry to stop killing us has moved beyond the people most harmed and into the mouths of those who once had the privilege not to see.

There is a bitter complexity in watching the country awaken more fully to violence that Black and Brown communities have been naming for generations, and seeing that awakening hastened because two white people were killed. It forces a reckoning with whose pain has historically been seen as exceptional and whose suffering was treated as ordinary background noise. I felt both relief that more people are finally paying attention and a quiet sorrow that it so often takes proximity to whiteness for America to recognize what was already unbearable.

It made me flash back to 30 minutes earlier, after leaving the airport in our rental car, when I witnessed a Minneapolis police squad car pull up next to us and honk in solidarity with ICE protesters. I didn't feel hope so much as psychological whiplash. This is the same city where Floyd's murder forced the world to confront what Black residents had long known about policing here. One organizer had already told me plainly: The police initially tear-gassed protesters demonstrating against ICE. The honk felt less like transformation and more like situational alignment, an institution reading the room, not rewriting its values. I couldn't help but think of how the Seattle Police Officers Guild's rhetoric has often doubled down rather than bent toward accountability, a reminder that institutional instincts rarely change. They adjust just enough to survive the moment.

The first lesson is that the movement in Minneapolis did not begin from nothing.

They'd of course been here before. Some caregivers, organizers, and clergy told me that the civic infrastructure that supports mutual aid and community care didn't spring up months ago. It was tested in the grief and uprisings after George Floyd's killing in 2020 and has only deepened since.

As the Rev. Oscar Sinclair, of Unity Church-Unitarian in St. Paul, told me, "There are two stories you can tell. One is that the accumulated grief is very real. There are a lot of unhealed wounds in this town. But the other story is that those repeated griefs tightened the civic infrastructure. The voluntary organizations, the partnerships — they were already in place. When this happened, they snapped back into motion."

Grief, here, has been an architect.

In Seattle, we still narrate tragedy as a rupture, an aberration in an otherwise intact civic story. In Minneapolis, people speak of it as exposure. It reveals who has already built the muscle of organizing, who has networks sturdy enough to bear weight, and who has learned, long before the sirens, to trust the person standing beside them.

"You can't create trust in a crisis. There isn't time to build relationships from scratch," Sinclair said. "You lean on the trust you already made."

Community as Strategy

I came with organizers from Common Power, a civic group that believes democracy is something practiced with bodies, voices, and courage. They'd organized a contingent of Seattleites, including members of the media, the Mayor's Office, and local Indivisible chapters. We weren't there as tourists of tragedy, but as observers of communal infrastructure: flesh-and-bone neighbors, parents dropping children off at school, people looking out for one another, and the deeper question of what it looks like when ordinary people become the systems that keep each other alive.

Outside the Whipple Federal Building, a drab, concrete federal office complex that has become the processing hub for ICE detentions in Minneapolis, the abstraction of policy met the full weight of human consequence. The morning I was there, the plaza was lined with bundled-up neighbors, protesters, and legal observers in bright vests, in costumes, carrying bullhorns. Volunteers passed out hot drinks. And all watched the steady movement in and out of a building most residents had never thought twice about before it became synonymous with families disappearing behind government doors. Every time an SUV crept toward the secured entrance, the crowd surged with chants and raw anger, grief sharpened into sound. The agents moved past, pretending to ignore the heckling and shouts of "traitors" and "shame," their faces obscured behind masks and tinted glass.

There, I spoke with Ifrah Abshir, once a Rainier Beach High School student organizer in Seattle, now rooted in Minneapolis, and the distance between the two cities seemed to collapse. She told me she learned how to organize back home and carries those same tools here, because what's happening now "is all xenophobia … a fear of Blackness," the same forces she confronted as a student fighting for Black lives and student dignity in Seattle. Watching Somali families targeted in Minneapolis, she said, felt like a larger-scale version of struggles she already knew, different geography, same logic of who is made vulnerable and who is expected to endure it.

That shared understanding, that survival depends on what ordinary people choose to do for one another, surfaced again and again in my conversations.

"Here, we don't ask each other, 'How are you doing?' When we see each other, we ask, 'What are you doing?'", a Minnesotan who asked not to be identified told me.

In this city, solidarity is not ornamental. It is something done in real time, in the cold of night after a food distribution, in walking teachers' aides to their cars, in ensuring that neighbors do not pass through terror alone.

"I saw people watching me in cars," Warsome, a Somali immigrant, told me. "We always carry our passports. We are targeted for our race, but white people can be so-called illegal too. White House has these orders — I can't believe this is America."

That sense of disbelief is an indictment of a moment where the very federal agencies that claim to defend us have become instruments of terror for so many neighbors.

And yet Minneapolis did not collapse into fear. People came out in subzero temperatures to turn houses of worship into food centers.

At a Dios Habla Hoy Church in South Minneapolis, a primarily Latino congregation, Common Power and local volunteers formed a human chain from a loading dock to a parking lot, passing boxes filled with milk, potatoes, and paper towels into waiting cars. Families too afraid to leave their homes had filled out online forms; strangers now mapped their neighborhoods by need.

Church pastor Sergio Amezcua, a reformed Trump supporter who organized the effort, told me, "We're preaching with action. It's time for Christians to talk less and love more. You cannot say you love God while hating your neighbor. If you're cheering policies that hurt immigrants, you would've been cheering when they crucified Jesus too."

He said that the church has delivered nearly a million pounds of food over the past two months. It also helps with rental assistance for people unable to hold jobs because of their immigration status.

"This isn't politics for us. These are families who can't work, who are about to lose their homes. If we don't show up for each other, we're going to have a humanitarian crisis in our own city."

This was a lesson in what happens when fear meets structure. Fear without structure collapses inward. Fear with structure becomes mutual aid.

The Fear of Forgetting

Even as I admire this, part of me is gripped by fear of the familiar drift, the slow slide back into a terrible normal where the urgency fades, the vigils thin out, and the systems that produced the harm settle back into place, largely untouched. I remember how, after George Floyd's murder, there was talk of reckoning, of transformation, of a country finally ready to confront itself, and how quickly so much of that energy was absorbed into statements, task forces, and time. That fear hums under everything now: that once the headlines cool and the immediate crisis passes, people will return to their private lives and call it healing.

It stays with me when my Lyft driver, taking me to my next destination, brings up Floyd and tells me he has become "an afterthought" amid all that is unfolding. It settles deeper as I stand alone in the frigid air at George Floyd Square, watching drivers move past, eyes fixed on the road ahead, not the painted face of the man receding behind them.

But the Rev. Sinclair's words stay with me from an earlier conversation. He reminded me that 2020 was shaped by COVID-19, by isolation, by distance: a moment defined by disconnection. This time, he said, feels different: People are gathering, feeding one another, standing in parking lots and on sidewalks, choosing proximity over retreat. I want to believe that kind of connection is harder to forget, harder to unwind — that maybe, just maybe, we won't go back so easily this time.

Unity and Solidarity From Seattle

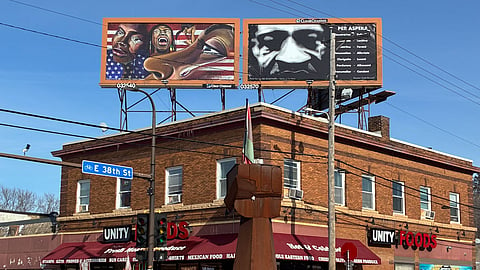

It felt fitting, in a way that was both tender and unsettling, that the first sign I noticed at Pretti's memorial read Unity and Solidarity From Seattle in red, white, and blue — a piece of one city's conscience set down in the grief of another. By the end of our trip, when I looked at the Seattle folks I'd traveled with, it seemed they were trying, in their own imperfect but earnest way, to live inside the promise those words carried.

Binh Truong, a general manager of fieldwork at Common Power, was 7 when her family immigrated from Vietnam and now lives in Columbia City. She said something that kept ringing in my chest: "It feels weird to say this, but [this trip] fills me with confidence."

Not because Minneapolis is somehow braver than Seattle, but because we watched how many different kinds of people can become part of a defense system, "from heads of known grassroots orgs … to the dude who's passing out granola bars and beef jerky and hot drinks at a protest site," a man who doesn't even call himself an organizer but shows up daily because, as she put it, "people expect this of me, and I'm happy to fill a need."

Truong's takeaway was blunt in the way real lessons tend to be: "We're bringing back a framework … some best practices … and we're going to stand it up. But even if we're not ready for it, the people will fill in the holes that they see." The framework matters, she told me — the trainings, the comms trees, the rapid response lists — but it only works if the city has the will to protect each other.

"If that desire is there with your neighbors, then a framework will go far, and infrastructure will go far. But if people don't have that desire in the first place, it's not gonna go," Truong said. That's the test she brought back to Seattle, not as rhetoric but as a map: South Seattle already has nodes — El Centro de la Raza, the Filipino Community Center, the Ethiopian Community in Seattle, Refugee Women's Alliance, the Rainier Beach Food Hub — and the question isn't whether we have "community," it's whether we can turn that community infrastructure into "response structure."

Kathleen Carson came to Minneapolis as a board member of Seattle Indivisible, but she sounded less like a strategist than a person trying to name something she'd seen and didn't want to lose. "I've been so incredibly impressed … by what I've seen people here do in terms of coming together as a community," she said. Her reasons were twofold: "What lessons can we learn … in preparation, hopefully, that we would never need? … And the other is to really just come be in solidarity with them."

She kept returning to a sentence that has no glamour but all the truth: "We keep us safe." And she described Minneapolis as a place where people claim that responsibility — not just as a slogan, but as a muscle they've built through repetition. "They put out a call for 40 volunteers at the last minute, and 100 people show up … on a weekday," she said. "In a neighborhood, where something like 20% of people are in their rapid response."

For Carson, the lesson for Seattle wasn't to mimic Minneapolis's tactics like a template — no two cities are alike, after all — but to scale up our participation until our politics can't stay theoretical. "I can't imagine sitting it out," she admitted, talking about her own anxiety and how action becomes a kind of grounding.

Then, she said the part Seattle needs to hear most: "Our greatest weapon against fascism is that we smile at the stranger and we say hello. … There's a banality of goodness." She wasn't excusing empty performance — she was naming the pipeline. If your activism begins and ends with a yard sign, the answer isn't to shame you for being a beginner; it's to pull you into relationships until you can't pretend you don't belong. "My goal is to get the 'normies' — people who don't see themselves as activists — activated," she said, because "if you start with 'you have to be radical,' they don't come in." And once they do come in? "You can radicalize them." Not with slogans — with people. With names. With meals.

Matthew Oudkerk, one of the younger Common Power organizers, put it in the language of sound and pressure. "The moment always exists," he said. "Sometimes the volume is up a little higher." At 24, he's already learned that people react when the dial is loud enough — and that privilege determines who gets to wait for the noise. "Those of us who are privileged enough … to do people work … mutual aid, whatever your avenue is … we find those moments as opposed to allowing the moment to get to us." That's not hero talk. It's a discipline. And it's also a warning to Seattle: If we wait until the dial is screaming, we'll be trying to assemble trust in the middle of fear.

He wasn't romantic about what we saw at the memorials either. "Being here in person and walking in the places where these things happen … adds the most reverence and context to the work," he said. And then, honest in a way that made me look away: "I don't think I'll ever truly process it." He described how grief lands for people who keep moving anyway — "slow processors," he called us — and how emotions arrive "in weird moments … when it's ready to come out." But what he carried back to Seattle wasn't a clean moral. It was the memory of faces at Renée Good's memorial, and the strange power of recognition across differences.

He watched two women crying and felt something click: "They get it. … They understand what it feels like to look at this face and see a daughter that could be theirs." And then he made it practical. That feeling — the sudden collapse of distance — is what "is going to continue to drive me in Seattle … to show up with people as much as possible, regardless of what they look like." He was careful, too, to name the hierarchy of harm: "Some of us need it more than others … and I'm not going to ignore that." But he refused the lie that this can be fought alone: "This movement is about all of us coming together."

And then there was Matt McIntosh, the mayor's community relations manager, whose presence on the trip was its own kind of signal. The official reason for coming was simple: "If a similar amount of ICE presence were to arrive … we need to do absolutely everything that we possibly can to be prepared."

Reeling from the recent killings of the two young men in Rainier Beach himself, he didn't pretend grief was manageable either. "American society is just way too damn violent," he said, and then he admitted the truth that public life tries to bury: "It's more than I think anybody can actually metabolize. But it's essential to keep humanity at the forefront." Then, he framed the real task as two movements at once: tamp down the violence, yes, but also "gas up" the part of us that still knows how to care.

In Minneapolis, McIntosh told me he'd watched people make risk normal. "Trump and other folks … are going to do everything they can to convince us otherwise," he said. "But the dignity that folks are expressing … while dealing with that … I don't want it to be lost — the ways the folks who are being most targeted are also contributing to resistance … putting food on their tables, getting rent paid come hell or high water, and looking out for their neighbor."

Communities that care for each other refuse the illusion that safety is a luxury. Safety, in this sense, is mutuality: watching after children, delivering food, escorting folks home — the messy, everyday work of being human together. Communities that care for each other understand that the great challenger to despair is collective agency.

The Choice Before Us

And if that is what we choose, even as death brings us to our knees, we still stand. We stand because we lift each other. We stand because there are people willing to say, in the face of state violence: We will not let this be the end of our story.

Minneapolis offers Seattle a hard and necessary truth: We are not separate. Our neighborhoods are not islands. The grief in South Seattle is not contained by geography, and the loss on a Minneapolis sidewalk does not belong only to Minneapolis. In a country where death so often comes at the hands of those sworn to serve, we are reminded that dignity is not inherited from the state. It is claimed by the people.

And the work of claiming it does not begin in policy documents or press releases. It begins in whispered conversations between neighbors who understand they cannot wait for permission — that survival is something you practice together.

I thought about the two young men from Rainier Beach, about the families who now move through our neighborhoods with the same hollowed-out eyes I saw in Minneapolis. I thought about how grief travels, how it refuses to stay local, how it echoes from one memorial to another until it becomes a language the whole country is forced to learn.

Minneapolis did not give me hope in the easy sense. It gave me instructions.

Ask not 'How are you?' but 'What are you doing?' Know your neighbors before you need them. Do not wait for perfect politics to practice care. Understand that fear is a strategy — and so is solidarity.

The question before Seattle now is not whether we are progressive in theory, compassionate in branding, or vocal in moments of spectacle. The question is whether we will practice communal integrity, whether we will live up to the values this city claims as its own when it is inconvenient, uncomfortable, and costly.

Because civic integrity is not what a city says about itself. It is what a city does when its neighbors are afraid.

Seattle, we must choose.

And soon.

The author was invited to join a delegation of leaders, activists, and other media on this visit to Minneapolis. Common Power paid for his flight and lodging. The South Seattle Emerald maintains full editorial control of its coverage, including this story.

Marcus Harrison Green is the founder of the South Seattle Emerald.

No Paywalls. No Billionaires. Just Us.

We're raising funds to hire our first-ever full-time reporter and grow our capacity to cover the South End. Support community-powered journalism — donate today.